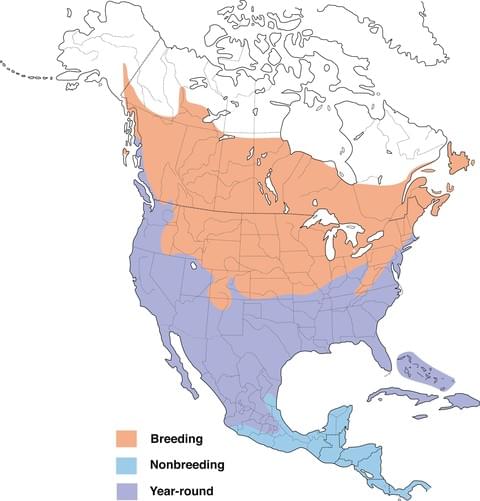

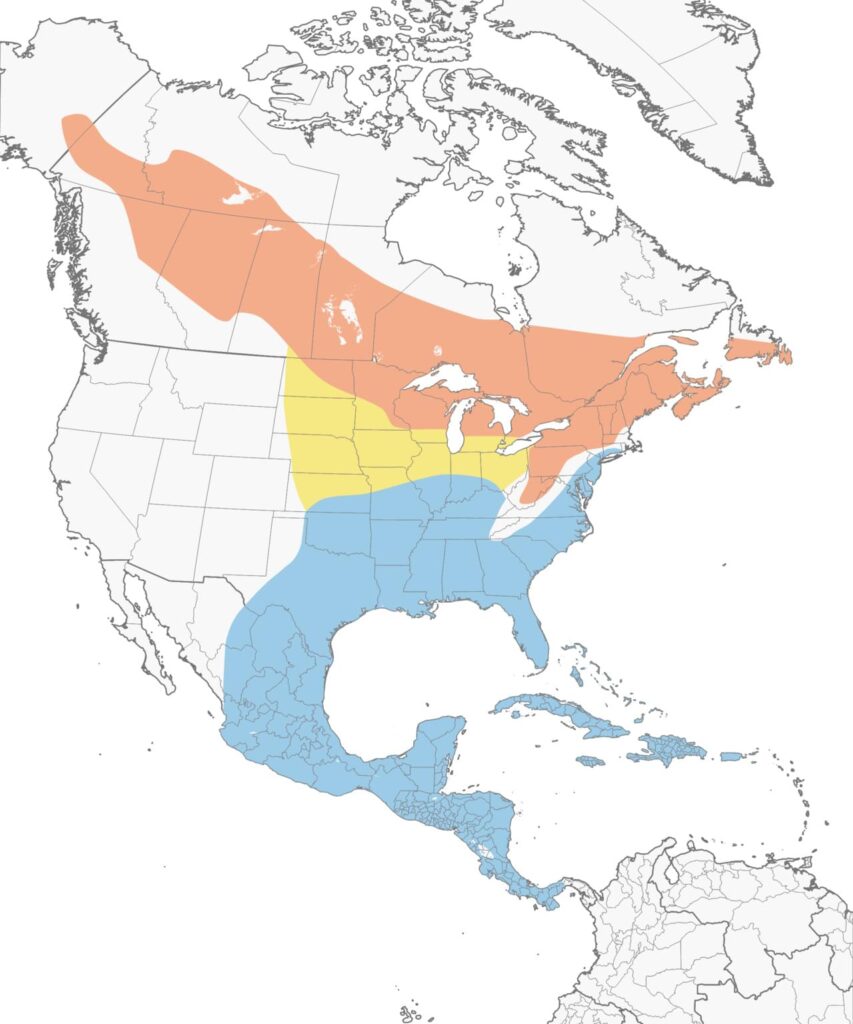

Another early Spring migrant, Killdeer have returned to Michigan for purposes of breeding. This common plover is the shorebird that is most associated with our neighborhoods and can be found in fields, playgrounds and golf courses. They are a shorter distance migrant as their range map shows; hence, the early return.

Hearing their call overhead as they fly, their name-sake “Kill-deer, kill-deer”, brings an uplifting feeling to me. This bird has made the journey successfully and hopes to find a suitable place to nest. Nesting for killdeer is a very plain affair – a simple scrape to lay the eggs in, with the male bowing forward and puffing his chest out, scraping backwards with his feet as the female watches. If he meets her approval, she will take his place and scrape a little herself. Mating then occurs. Once the eggs are laid, Killdeer may add rocks, bits of shell or sticks to the nest area.

In an attempt to keep the nest safe, Killdeer will engage in a broken-wing display, fanning their rusty colored tail feathers and walking as if they are injured in an attempt to make themselves look like easy prey and pull attention away from the nest.

In an attempt to keep the nest safe, Killdeer will engage in a broken-wing display, fanning their rusty colored tail feathers and walking as if they are injured in an attempt to make themselves look like easy prey and pull attention away from the nest.

The eggs are well camouflaged as you can see in this photo that shows adult, young and eggs.

The young killdeer are altricial when born, defined as able to walk and covered with fuzzy down. They immediately begin to follow their parents who will show them how to find food, consisting primarily of invertebrates including worms, snails, grasshopper, beetles, and aquatic insect larvae.

The young killdeer are altricial when born, defined as able to walk and covered with fuzzy down. They immediately begin to follow their parents who will show them how to find food, consisting primarily of invertebrates including worms, snails, grasshopper, beetles, and aquatic insect larvae.

Educating those who are able to make the decision not to spray pesticides on the fields and lawns where these birds find their food would be a great way to save this bird from harms’ way.

Educating those who are able to make the decision not to spray pesticides on the fields and lawns where these birds find their food would be a great way to save this bird from harms’ way.

Photo credits to Bill Creteau, Jerry Jourdan and Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Thanks to Ernie Sereniak for this unique photo of a Bald Eagle on ice

Thanks to Ernie Sereniak for this unique photo of a Bald Eagle on ice

te line of feathers that runs from the beak and across the cheek.

te line of feathers that runs from the beak and across the cheek.